The secret tunnels of Rufford in Lancashire

in the late 1960’s and early 70’s my childhood was centred on the village of Rufford. There are far more adventurous folk than me who may know more about the folklore of the tunnels, here are mine.

Let’s talk about historic local myths that I recollect from my experiences in the village of Rufford in the period 1962 to 1975.

Attending the local school, playing cricket and football, Friday evenings at the youth club and a very brief spell with the cubs. All allowed me to feel part of the village and its daily life.

Mates lived close by in Holly Lane, Liverpool Road, Church Road, Highsands Avenue, Cousins Lane, Brick Kiln Lane.

I remember having my haircut at the Fermor Arms by the manager, Tommy Kenny, with me sat on the bar on a Sunday lunchtime. Just to say I was with my Dad. I would later go on to play cricket with Tommy’s sons, Ronnie and Terry. It was also my privilege to coach his grandson, Rob.

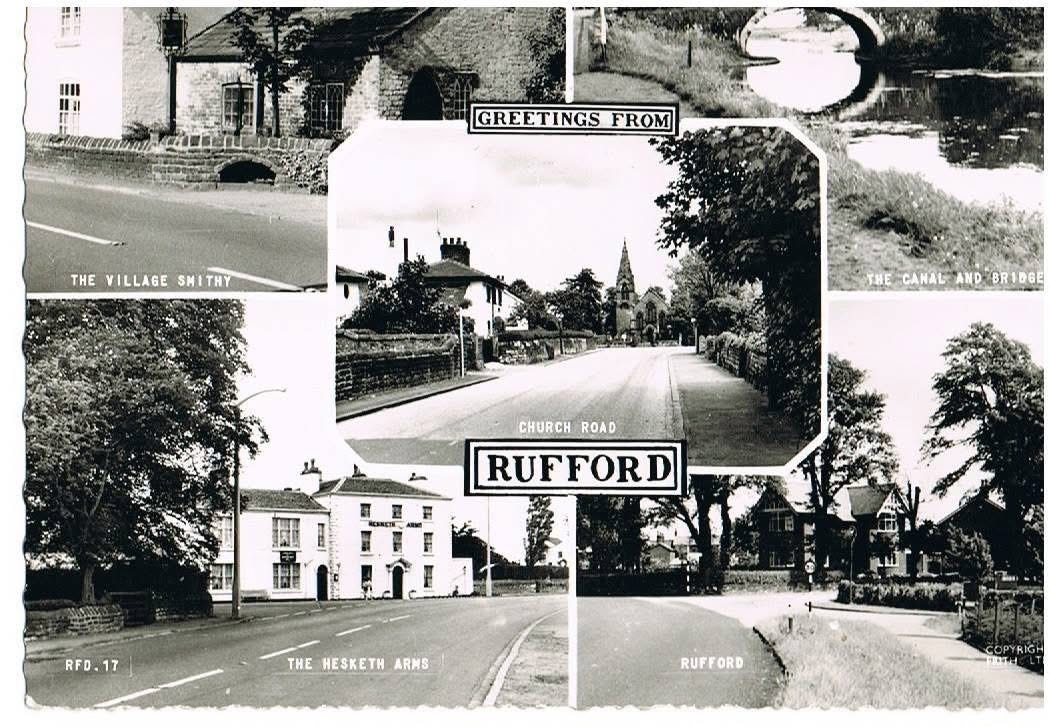

But I wasn’t a one pub lad, I was a regular at the Hesketh Arms, were I would muck around with the Barker boys, Simon, Adam and Andrew. Their grandparents, Mr & Mrs Wallace, were the landlords, with their parents as managers. Through them I would meet Glyn Lloyd of Apple Cottage - a lifelong friendship that continues to this day.

With barns, sheds and the cellar the Hesketh Arms was a veritable treasure for young boys to explore.

And we did explore but to be honest Simon and Glyn were fearless whereas I was more cautious and reflective.

Their exploring was to me “legendary”

In the cellar they discovered a tunnel entrance that was blocked off after several yards. As recently as last week, I spoke with Glyn who vividly remembers a 3ft square tunnel entrance.

That discovery convinced us that we had found the tunnel linking the Hesketh Arms to the Church and then onto the Old Hall.

In the early 70’s Simon and Glyn started digging their own tunnels in the land next to Apple Cottage; perhaps looking for a secret tunnel?

The tunnel became a labyrinth and a wonderful den. It could be quite a scary place but one that always makes me smile.

Local folklore in Rufford, Lancashire, speaks of a secret tunnel connectingRufford Old Hall, St. Mary’s Church, and the Hesketh Arms. These tales often suggest that the tunnel dates back to the era of Oliver Cromwell and the English Civil War, implying it was used for clandestine movements or as a refuge.

Rufford Old Hall, constructed around 1530 for Sir Robert Hesketh, is a Grade I listed building with a rich history. The Hesketh family, prominent in the area, were lords of the manor of Rufford from the 15th century. The hall features a Great Hall, which is the oldest surviving part of the structure.

St. Mary’s Church, located near Rufford Old Hall, has historical ties to the Hesketh family. The church’s heritage is closely linked to the family, and it stands adjacent to the hall. The current building was re-consecrated in 1873, replacing earlier structures that had stood on the site for centuries.

The Hesketh Arms, a Grade II listed inn, is situated in Rufford and dates back to the late 18th century. It has been a central part of the village’s social life for many years.

Despite the intriguing nature of these tunnel stories, there is no concrete historical evidence or documentation to confirm their existence. Such legends are common in areas with rich histories, often capturing the imagination and adding an air of mystery to local landmarks.

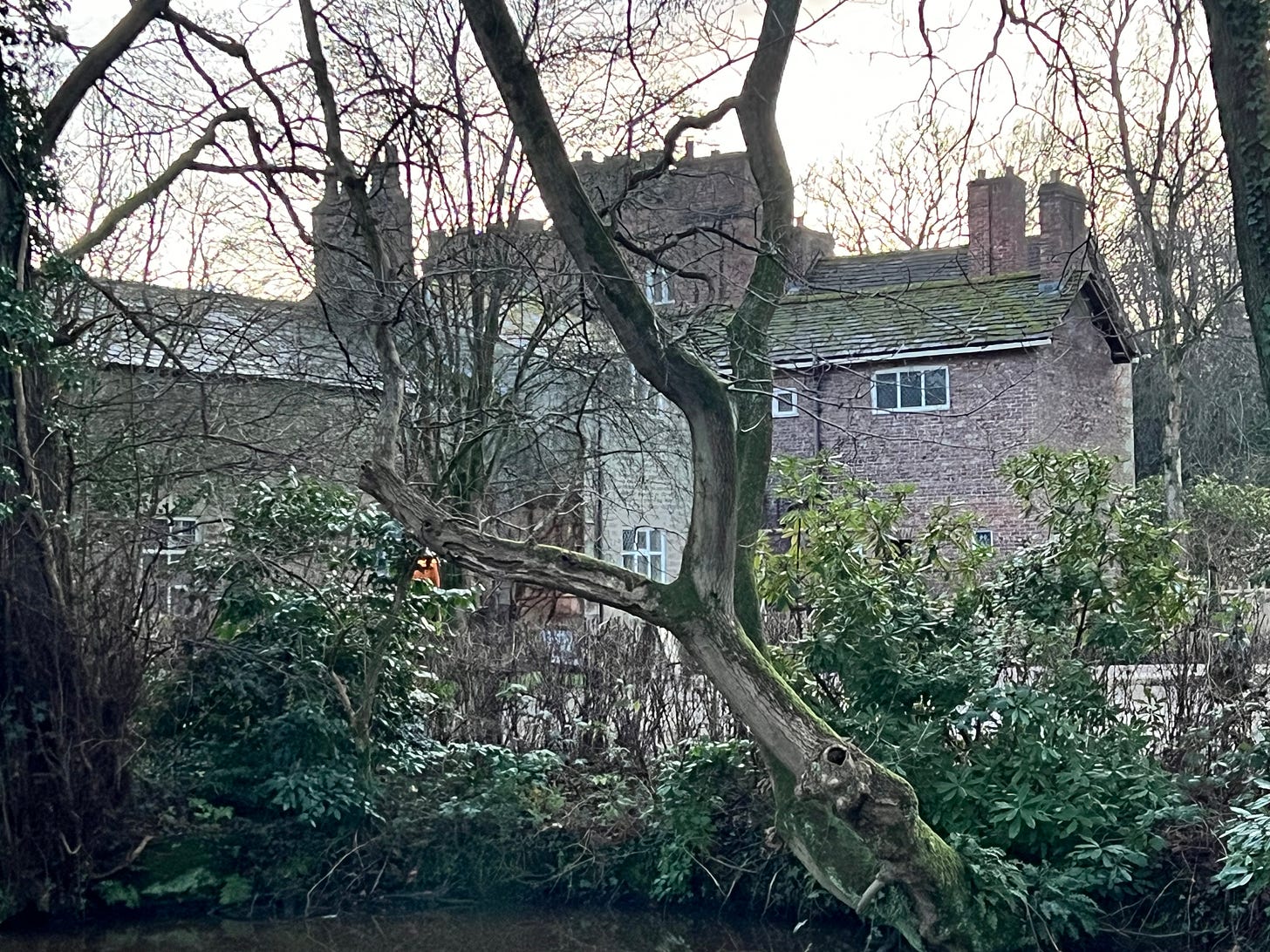

It’s worth noting thatRufford Old Hall does have a known secret chamber, discovered above the Great Hall in 1949, which was used as a priest hole in the 16th century. However, this does not confirm the existence of tunnels connecting the hall to other buildings. Additionally there are tales of tunnels linking the Old Hall with the New Hall. The grounds of the New Hall were known as the hospital grounds and to me in the late 60s and early 70s were out of bounds.

In the hospital grounds there were cracking conker trees to be investigated but as kids we were warned off either officially or a local myth.

There seemed to be hidden treasures that were being kept away from us - some things don’t seem to change. Perhaps it was a view that there were hazards; pond or lakes, the ice house and dare I say it entrances to tunnels.

The ice house is only one of three that now exist in the area and is subject to a grade 2 historic listing. The ice house within the grounds of Rufford New Hall in Lancashire is a notable example of 18th-century estate architecture, reflecting the period’s methods of food preservation prior to modern refrigeration.

Construction and Design

• Date: Likely constructed in the late 18th century, possibly around the same time as Rufford New Hall, which was built in 1760.

• Structure: The ice house features an egg-shaped subterranean chamber made of brick, accessed via a brick-vaulted passage on the northwest side. The entire structure is covered by an earth mound, providing natural insulation.

• Surroundings: Encircling the ice house is a circular ha-ha approximately 35 meters in diameter, with a low sandstone rubble wall. This design element served both aesthetic and practical purposes, maintaining uninterrupted views while keeping livestock away from the structure.

Historical Significance

• Purpose: Ice houses were essential for preserving perishable goods before the advent of mechanical refrigeration. During winter, ice would be collected from local sources and stored in the chamber, remaining frozen for use throughout the warmer months.

• Heritage Status: The ice house at Rufford New Hall is designated as a Grade II listed building, recognizing its historical and architectural importance.

Preservation

• Current Condition: The ice house remains a significant historical feature within Rufford Park. While access to the interior may be restricted to preserve its condition, the external structure and surrounding ha-ha are of interest to visitors and scholars alike.

• Conservation Efforts: Listing the ice house as a Grade II structure ensures that any alterations respect its historical integrity, safeguarding it for future generations.

The Tunnels Between Rufford Old Hall and Rufford New Hall: Myth or Reality?

These are historic landmarks steeped in stories and local folklore. Among the most intriguing legends associated with these estates is the existence of a secret tunnel system connecting the two halls. These tunnels, rumored to have been constructed centuries ago, are thought to have served as escape routes or means of discreet travel for the Hesketh family, the long-standing owners of both properties. While evidence of these tunnels remains elusive, their story offers a fascinating glimpse into the area’s history and the cultural imagination of the community.

Historical Context

The old hall served as a focal point of social and political life during the Tudor and Stuart periods. By the 18th century, the Hesketh family constructed Rufford New Hall, about a mile from the Old Hall, reflecting their desire for a more modern residence.

During this era, the construction of underground tunnels was not uncommon, particularly in estates with prominent or politically active owners. Such tunnels were often used for:

• Escape Routes: During times of political upheaval, including the English Civil War, wealthy families often built secret passageways to evade capture or persecution.

• Religious Practices: In Catholic households like the Heskeths’, tunnels could provide clandestine routes for priests during periods of religious persecution.

• Practical Utility: Tunnels could also serve practical purposes, such as transporting goods, avoiding inclement weather, or ensuring privacy between properties.

The Legend of the Tunnels

Local folklore suggests that a tunnel system was constructed between Rufford Old Hall and Rufford New Hall. These tunnels are said to:

• Span approximately one mile, connecting the two estates discreetly.

• Include hidden entrances and exits within the cellars or grounds of each hall.

• Be large enough to allow people and possibly goods to travel through them.

Evidence and Speculation

Despite the compelling nature of the legend, no concrete archaeological evidence has been uncovered to confirm the existence of these tunnels. However, several factors contribute to the persistence of the story:

1. Architectural Features: Both Rufford Old Hall and Rufford New Hall have cellars and other structural elements that could suggest the starting points of tunnels.

2. Local Accounts: Stories passed down through generations often mention unexplained underground chambers or bricked-up passages.

3. Historical Precedent: The use of tunnels for religious and political purposes in Lancashire during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries adds plausibility to the idea.

In contrast, skeptics argue that the soft, marshy terrain of the area would make tunnel construction and maintenance difficult. Additionally, without documented plans or contemporary references, the existence of such tunnels remains speculative.

Cultural Significance

The legend of the tunnels contributes to the mystique of Rufford’s historical estates, drawing visitors and fostering local pride. It also reflects broader themes in English folklore, where underground passageways symbolize mystery, secrecy, and resilience.

Modern Investigations

Efforts to verify the existence of the tunnels have included:

• Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR): Modern technology could potentially identify subsurface anomalies consistent with tunnels, though no formal studies have been publicly documented.

• Architectural Surveys: Detailed studies of both halls have yet to uncover definitive evidence of tunnel entrances or pathways.

• Oral History: Collecting stories from local residents continues to provide valuable context, even if the accounts remain anecdotal.

The story of the tunnels between Rufford Old Hall and Rufford New Hall is a captivating blend of history and folklore. While no physical evidence has yet substantiated their existence, the legend endures as a testament to the area’s rich cultural heritage and the enduring allure of mystery. Whether the tunnels are real or imagined, their tale continues to spark curiosity and connect the past to the present, keeping the history of Rufford alive for future generations.

In summary, while the tales of a tunnel linking Rufford Old Hall, St. Mary’s Church, and the Hesketh Arms are fascinating and contribute to the area’s rich tapestry of folklore, there is no verifiable evidence to support their existence. A similar conclusion can be drawn about the tunnels between the old and new halls.

These stories remain a charming aspect of local legend, reflecting the community’s deep connection to its historical sites. More importantly the lack of verifiable evidence doesn’t change my childhood memories.

My own perspective is that the construction of the New Hall and the construction of the Rufford Branch Canal, there will have been hundreds if not thousands of workers.

Those will have been skilled and experienced in constructing ditches, drains, tunnels and of course canals.

If tunnels from the old hall were in existence before 1760, it does seem possible they could have headed into Rufford Park or headed to the church for example.

The New Hall, the Hesketh and the canal were all constructed between 1750 and 1785 so constructing new tunnels seems feasible. It was not just the New Hall that was constructed, there were lodges, barns, tennis courts, an ice house, ponds and a lake.

Those workers were available, skilled and more than capable of creating new tunnels or securing older tunnels. If the land was marshy, they were building a canal and drainage ditches plus a lake; ideal for providing more suitable ground for secret tunnels.

In the 1700s, workers constructing canals in Britain were often referred to by several nicknames, reflecting their tough, physically demanding work and unique lifestyle. These nicknames include:

1. “Navigators” or “Navvies”

• Origin: The term “navigator” initially referred to workers building navigable waterways (canals) during the 18th century. It was later shortened to “navvy.”

• Meaning: This became a widespread term for canal laborers and, eventually, for workers involved in other major civil engineering projects, such as railways and roads.

• Connotation: “Navvies” were known for their hard physical labor, resilience, and nomadic lifestyles, as they moved from project to project.

2. “Ditchers”

• Origin: Many canal workers were involved in digging and shaping the canals, which resembled large ditches.

• Meaning: This nickname emphasized their role in excavating and constructing the waterway channels.

• Connotation: It highlighted the practical, unskilled nature of much of the labor.

3. “Cutters”

• Origin: Refers to the task of “cutting” through earth and rock to create the canal routes.

• Meaning: This name was particularly applied to those who worked on heavy excavation projects, such as cutting through hills or rocky terrain.

• Connotation: It acknowledged the intense, backbreaking effort required for such tasks.

4. “Muck Shifters”

• Origin: Informal term for laborers tasked with moving large quantities of soil and debris (“muck”) during excavation.

• Meaning: This nickname was often used humorously or colloquially.

• Connotation: It conveyed the messy and grueling nature of their work.

5. “Hod Carriers”

• Origin: Though more commonly associated with bricklayers, this term was also used for workers who carried tools, stones, or soil to and from construction sites.

• Meaning: Reflects the support role of some workers in the canal-building process.

• Connotation: It suggested less skilled but equally essential labor.

Lifestyle and Legacy

• Canal construction workers often lived in temporary camps near the worksite, leading to a distinctive culture and sense of community.

• They were known for their strength, endurance, and a reputation for rough behavior, which added to their legendary status in British labor history.

• The term “navvy” remains an enduring symbol of hard, manual labor and is still recognized in modern English.

These nicknames, while descriptive, also reflect the camaraderie and rugged life of canal workers, whose efforts transformed Britain’s infrastructure in the 18th and 19th centuries.

That availability of skilled labour would easily allowed the construction of secret tunnels.

Even today there are drainage tunnels beneath Liverpool Road feeding into the Old Hall grounds. But how do we get verifiable evidence in the year 2025.

What staggers me today is that modern myth is being created, or should it be described as rumour on a daily basis.

It can be word of mouth or the modern day phenomena that is social media.

Take, for example, the current rumours about the Hesketh Arms and its closure for renovations - there are so many!

Twenty years ago many of us thought we had lost the Hesketh forever - a village without a pub, a village losing its resources on a regular basis. New houses appearing with no perceivable resources being added.

A courageous renovation, however, gave the Hesketh back its life and breathed new energy back into the village.

If rumours are to be believed a next renovation is on its way; please keep the cellar and the excellent cask ales, the open kitchen and pizza oven are not to my taste but I am not complaining.

A bigger bar, a tap room (or is it a snug or a dogs den?) and hotel rooms add to the rumour mill.

Practically the toilets need upgrading and a new dryer in the men’s room would be welcome. Oh and did I mention painting; inside and out.

Outside expertly manicured gardens are part of the rumours. A new surface for the car park and here’s why these rumours are included; they need to dig new drains

Now that’s how you find secret tunnels

Great read ...some very familiar names too ..We lived in The Flash in the house where Glyn now lives ....my brother used to be pally with Glyn ...Andy Harker .....I still think of Rufford as home having been in Scotland for nearly 50 years

Really interesting article , thank you. We are new to the village having only lived here for 30 years 😂. Can you recommend any books on the history of the village?