Episode 1: From the Andes to the Mere

How the potato travelled across oceans, through history, and found its place in Rufford soil.

Long before a spade ever broke the mossy ground of Rufford, the potato began its global journey high in the Andes Mountains of South America. There, for over 7,000 years, Indigenous communities—including the Inca—cultivated a wide variety of tubers adapted to extreme conditions.

The Spanish brought potatoes to Europe in the late 16th century, likely around 1570. Their spread across the continent was slow at first. Suspicion and myth surrounded the crop—many believed it was harmful, associated it with leprosy, or deemed it fit only for livestock. Some even planted it for its decorative flowers (famously, Marie Antoinette wore potato flowers in her hair).

By the early 1600s, potatoes were being grown in small pockets of England and Ireland, though uptake remained cautious. The story that Sir Walter Raleigh introduced the potato to Britain is probably apocryphal, though it is often repeated.

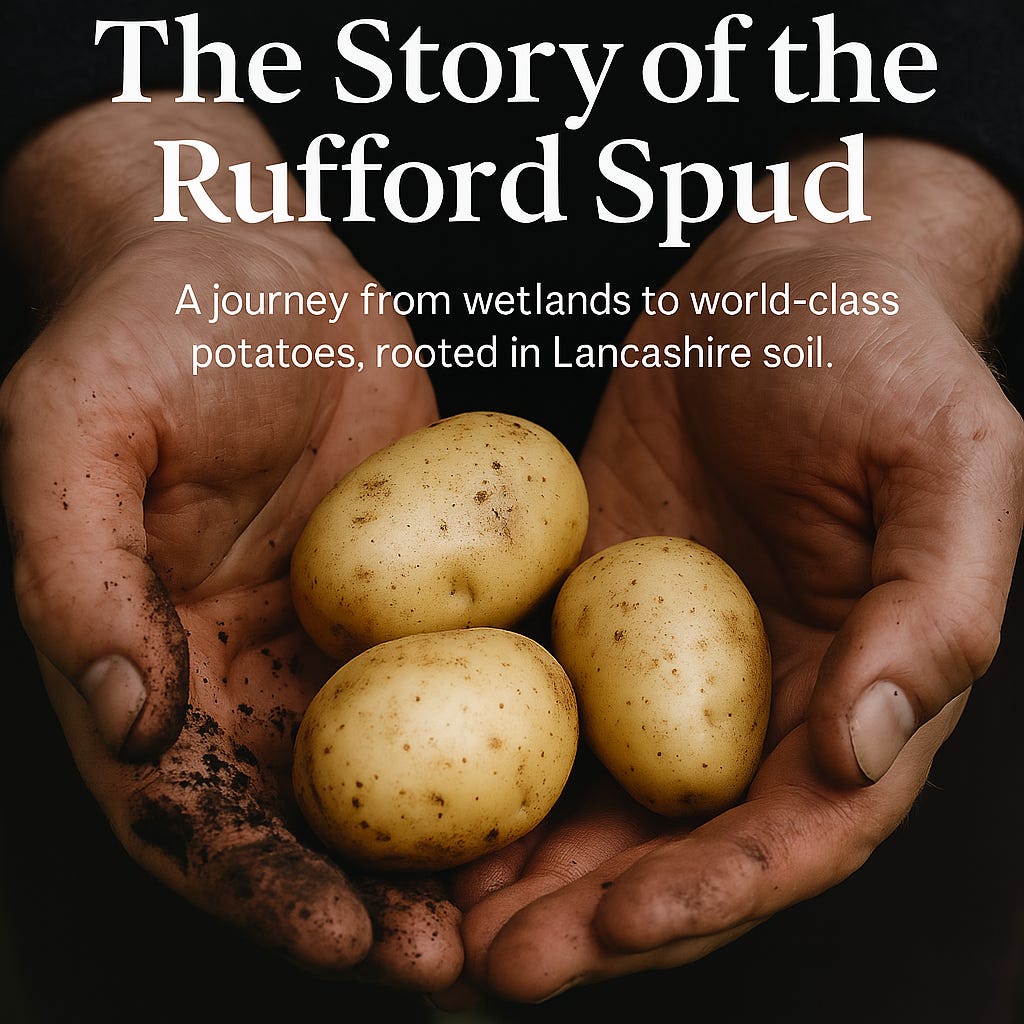

Martin Mere, located near Rufford in Lancashire, has undergone a remarkable transformation—from a vast freshwater lake to a renowned wetland nature reserve. Historically, Martin Mere was the largest body of fresh water in England, covering approximately 15 square miles. Formed at the end of the last Ice Age, the mere was a significant feature of the West Lancashire Coastal Plain.

In the late 17th century, efforts to drain the mere for agricultural purposes began. Thomas Fleetwood of Bank Hall initiated the first major drainage scheme in 1692 by cutting a channel to the sea. These efforts continued into the 18th and 19th centuries, with steam pumps eventually being employed to reclaim the fertile land for farming. Let’s look at how this connected with the establishment of the River Douglas Navigation and the Rufford Branch Canal.

The Battle to Drain Martin Mere

How men with shovels, sluices, and steam took on England’s largest lake—and why potatoes followed

In the late 17th century, Martin Mere was a vast inland lake—15 square miles of shallow water, reeds, and mossland. It was the largest freshwater body in England, shaped by the last Ice Age and fed by the River Tawd and other small waterways across the West Lancashire plain. To those farming higher ground, it was an untapped opportunity. To others, it was wild beauty.

In 1692, Thomas Fleetwood of Bank Hall led the first major attempt to drain the mere. Using basic tools and ditches, he carved a channel to the sea at Crossens. It was ambitious—but short-lived. The water returned.

Over the following century, new drainage attempts were launched. In the 1780s, Thomas Eccleston of Scarisbrick Hall revived the effort. Now backed by more capital and experience, these ventures sought not only to reclaim farmland, but also to manage trade and flood risk across the mosses.

The turning point came with steam. By the mid-19th century, the introduction of steam-powered pumps enabled engineers to continuously remove water and maintain low water tables. The land was finally usable on a reliable scale. Potatoes thrived in the light, peaty soil left behind .

The story of Martin Mere is inseparable from the creation of new transport routes. The River Douglas Navigation, authorised in 1720 and completed in 1742, helped link Wigan’s coalfields to the Ribble estuary. By the 1760s, the Rufford Branch Canal was being cut to provide reliable access to Sollom and Tarleton, bypassing the tidal limitations of the River Douglas. The canal extension reached Rufford by 1781, and in 1805, the final connection to Tarleton completed the loop .

These changes brought mossland farmers new routes to market. Crops, including potatoes, could now travel more efficiently from field to town via canal barge. Reclaimed from water, the flat fields around Rufford and Holmeswood became some of the most valuable early-cropping farmland in the country.

The drained landscape remained primarily agricultural until the 20th century, when conservationists recognised its potential as a habitat for wildlife. In 1972, the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT), founded by Sir Peter Scott, purchased 363 acres of the former mere for £52,000. The WWT aimed to restore the wetlands and create a sanctuary for bird species. By March 1975, the WWT Martin Mere Wetland Centre opened to the public, offering visitors the chance to explore diverse wetland habitats and wildlife.

Today, WWT Martin Mere spans over 600 acres and is designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), a Special Protection Area (SPA), and a Ramsar Site, reflecting its international importance for wildlife conservation. The reserve is home to more than 2,000 species of birds, mammals, insects, fish, amphibians, reptiles, and other wildlife. Notably, it serves as a wintering ground for thousands of pink-footed geese and whooper swans migrating from Iceland.

In addition to its rich biodiversity, Martin Mere offers educational programmes and interactive exhibits, fostering public awareness and appreciation of wetland ecosystems. The centre’s commitment to conservation and education has made it a vital resource for both the local community and visitors from afar. As of March 2025, WWT Martin Mere celebrates its 50th anniversary—marking five decades of dedicated efforts in wetland restoration and wildlife preservation.

Martin Mere’s transformation is undoubtedly linked to the history of potato farming in Rufford and Holmeswood.

It wasn’t until the 18th century that the potato began to take hold in Lancashire. Here, it found ideal conditions: cool temperatures, consistent rainfall, and fertile soils. The West Lancashire Plain, stretching from Southport to Rufford, offered especially suitable terrain.

In Episode 2:

More memories of Martin Mere

The impact of the Industrial Revolution on Rufford

The local history of Potatoes until the 1920’s

Sources:

Wikipedia – Martin Mere: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Mere

Canal & River Trust – Rufford Branch: https://canalrivertrust.org.uk/canals-and-rivers/rufford-branch-leeds-and-liverpool-canal

Scarisbrick Parish Council – Martin Mere and Flood History: https://scarisbrickparish.gov.uk/flood-threat/history

Virgoe, R. – Thomas Eccleston and Mossland Reclamation in Lancashire, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire (HSLC)

Salaman, R.N. The History and Social Influence of the Potato (Cambridge University Press, 1949)

Reader, John. The Untold History of the Potato (Vintage, 2009)

National Trust – “The Potato’s History”

British Library – Food in Industrial Britain

Kew Gardens – Crop Origins Database

Frank Ashcroft’s (Grandad’s) new potatoes 🥔 will never be beaten for me. When Grandma made mince, peas and new potatoes from the garden picked 30minutes earlier.

Very informative Mark, I love the Rufford new spuds, gently boiled and tossed in salty butter!! Roll on spud season 😎🙏