There’s a smell you never forget. A Rufford kitchen in the 1950s was something my Uncle Albert would recall in 1979, as the two of us delivered Ainscough’s flour to a bakery in Chester. Uncle Albert was driving for Caunce of Rufford, and I was his second man during the summer holidays.

It wasn’t just the potatoes. It was the clatter of a pan on the hob, the steam rising from a colander in the sink, the comforting whiff of lard pastry browning in the oven. Kitchens were the beating hearts of our homes - more than dining rooms or parlours. It was in the kitchen that the coal fire glowed, the wireless crackled out the afternoon play, and wartime frugality slowly gave way to something like hope.

Potatoes, of course, were ever-present. On Mondays it might be bubble and squeak, packed with Sunday’s leftovers. Midweek meant a deep pie of potato and onion with a thick crust and a flick of salt on top. And on Fridays, Mum might slice spuds into thin cakes, fry them in dripping, and serve them with pickled onions from a jar she insisted was older than me. Recipes weren’t written down - they were passed from hand to hand, kitchen to kitchen. Even now, I can close my eyes and taste those lumpy mashed potatoes, beaten with a fork and softened with milk from the churn.

From Spuds to Studs: The Day They Won Twice

Not all glory in Rufford came from the land. Some of it was earned in boots caked with chalk and clay, beneath skies as grey as the Ferguson tractors parked nearby.

Forty-five years after the war, they still talked about it - the day Rufford’s village footballers won not one, but two cup finals in a single afternoon.

It was a warm Saturday, the kind that smelled of cut grass and liniment. The first final kicked off at three o’clock sharp - the Skelmersdale Medal competition against Ormskirk St. Anne’s. It was a bruising game, all elbows and grit, and it went to extra time before Rufford edged ahead 4–3. But the victory brought no rest. There was barely time for a pint, let alone a team talk.

That same evening, they took to the pitch again; this time against Rainford, in the Burscough final. The legs were heavy, the lactic acid unforgiving. After another drawn-out contest; 2–2 after extra time - the result came down to a coin toss. One flick of silver in the dusk light, and Rufford had done the impossible. Two trophies. One day. The same eleven players.

The names still echo in parish halls and old photograph albums: J. Mason, W. Ashcroft, J. Fairclough, H. Gaskell, G. Gaskell, Jack Mason, J. Parr, L. Sewell, F. Postlethwaite, G. Hitchen, H. Caunce, J. Martland, and E. Hitchen. In the front row: T. Swift, W. Gibbons, F. Lea, and B. Harrison - the lads who made it happen.

Walter Gibbons, one of the heroes that day, later turned to breeding exhibition budgerigars. But he kept the team photo framed on his mantelpiece. “Best birds I ever raised,” he used to say, “but they never won me two finals in a day.”

It wasn’t just a sporting story. It was a story of endurance, of community, and of the belief that effort matters - even when the scoreboard doesn’t tell the full tale. And in Rufford, that belief ran deep, whether in boots or boot soles.

From the Liver Building to Junction Lane

In 1953, my mum left Aughton behind and headed for the city to work. Only 18 years old and already full of quiet ambition, she took a job as a secretary in the Royal Liver Building with John Holt & Co., an old shipping and merchant firm with deep colonial ties. She caught the early train from Town Green Station into Liverpool each morning - glancing at the fields and pumps of the farms from the carriage window; and climbed the steps of that vast stone fortress on the Pier Head, shoulder to shoulder with other young women in smart coats and heels.

Inside, she typed letters on an upright Remington, filed purchase orders, and learned the rhythms of international trade. Liverpool in the mid-50s was noisy and thrilling, and for a time, she thrived in it. But after a few years, the tide turned. Maybe it was the grind of the commute. Maybe something closer to home tugged at her.

By the late 1950s, she was back in West Lancashire, working for Shepherds in Burscough - the giant wooden handle factory on Junction Lane. A new chapter was beginning.

A Meeting at the Works Do

My father was already back on the land. Having served in the REME and returned to civilian life with more practical skills than patience, he found work not far from Rufford, hauling produce.

They met on a blind date; courtesy of my Auntie Nellie and Uncle Walter. No fuss, no fanfare. Just bus rides, long walks, and the occasional trip to Southport when they could spare the money.

Sport and the Spirit of ’66

The early years of their relationship were framed by football and cricket. Saturday afternoons saw men on the field and women on the sidelines; though not always as spectators. Some of the most cutting match analysis I’ve ever heard came from my mum. And did I mention the cricket teas at Rufford Cricket Club?

Dad would talk about local lads who were well known for their football; two were always prominent; Bobby Langton and Larry Carberry, the boy from Burscough who went on to help Ipswich Town win the Football League under Alf Ramsey. He was a local hero, quiet but determined. A right-back with boots full of mud and grit.

As the years passed, the country began to stir with excitement. England’s national team was on the rise. By the mid-60s, every pub and barber’s shop was buzzing with predictions and patriotism. In our family, football wasn’t just a game; it was a language. And in 1966, it spoke to us all; me included.

Tying the Knot

Mum and Dad married on March 9, 1957; a modest ceremony, no limousines or big bands. Just St Michael’s Church in Aughton. My godfather, Bob Rimmer, and my mum’s sister Pauline were Best Man and Maid of Honour.

Their honeymoon was brief; the land doesn’t wait. But their lives were now joined; two branches of old West Lancashire families bound together under grey skies and hard-won smiles.

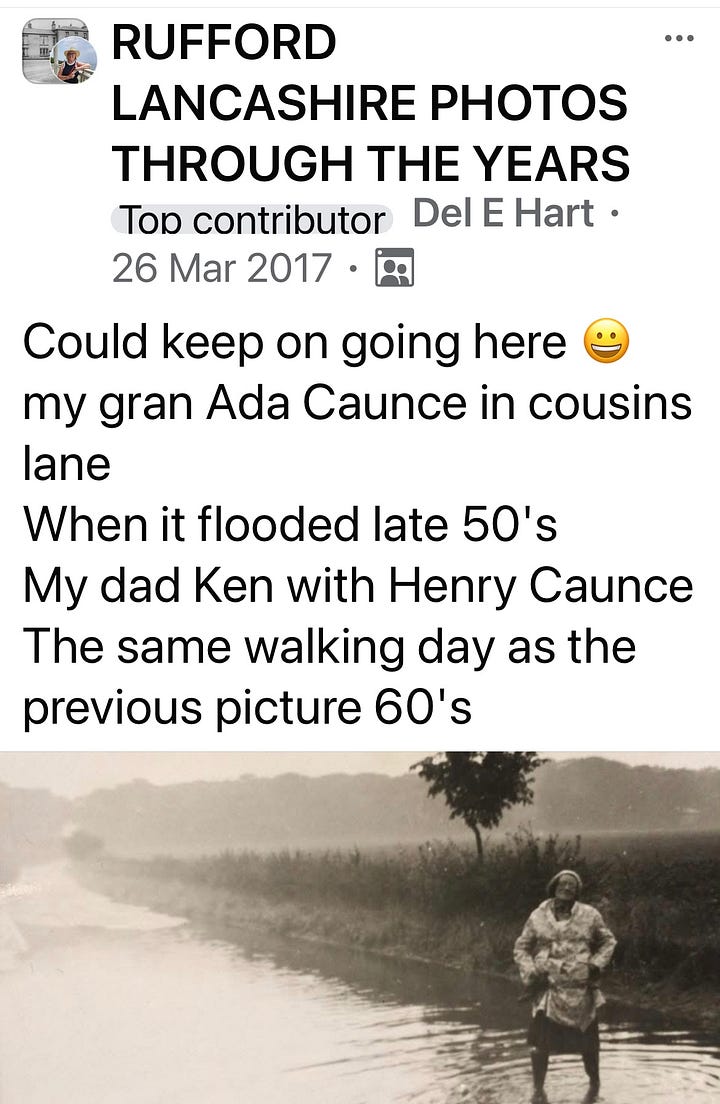

The Water Still Comes

That same autumn, the Mere misbehaved again.

There was a breach in one of the sluice banks and Martin Mere was underwater, destroying crops in an instant. Floods came down across Cousins Lane, the ditches overflowed, the low meadows drowned.

The farmers and the pump men worked around the clock to keep fields fit enough to cultivate. I remember tales of sandbags and wooden clogs soaked through, of a whole stack of seed potatoes floating down the track toward Holmeswood.

It was a reminder, as ever, that the land gave and the land took. Nothing in farming was guaranteed.

A Shift in the Soil

Yet progress crept in. New tractors, belt-driven and noisy, replaced the tired old horses. Fertilisers were trialled, sometimes with patchy results. Potato clamps became more structured, ventilation improved, and hauliers with wooden-bodied wagons began to form a new rhythm of collection and delivery. There were even whispers of selling to markets beyond Ormskirk; maybe as far as Manchester or even Birmingham.

Mum, ever practical, kept records. Dad was away during the week; they called it “trunk” travelling; up and down in an 8-wheeler between Glasgow and London. He worked for Woodcocks alongside mates from Rufford and Holmeswood; Bill Thompson, Gilbert Holden, and Harry Sharrock.

A New Arrival on the Horizon

By the end of the decade, something; or other someone was on the way. A child. A new generation. One that would grow up hearing tales of flooded fields, smoky stoves, lorries, cricket and Larry Carberry’s clean tackles.

A child who, many years later, would sit down to write the story of it all; with a mug of tea, a plate of hotpot, and a deep-rooted love for the Rufford spud.

Machines on the Farm

Talley Tractor – A Rarer Chapter in British Agricultural Mechanisation

Nestled among the better-known names like David Brown, Ferguson, and Fordson, the Talley tractor stands as a lesser-seen but equally evocative emblem of post-war British ingenuity. Likely produced in limited volumes during the post-1945 agricultural boom, the Talley illustrates the eclectic mix of makers described in British Tractors 1945–1965 - from mass producers to low-volume backyard enterprises.

Though it never reached industrial scale, the Talley’s design reflects the era’s priorities: robust mechanical simplicity, function over frills, and adaptability for smallholders or specialist farms. Its styling, with bolted-on features and upright geometry, suggests postwar production just before diesel engines and hydraulic lifts replaced belt pulleys and hand controls.

It likely used a petrol/TVO setup and a proprietary or reconditioned gearbox. The Talley remains a symbol of Britain’s tractor story: small-scale ambition in a moment of national mechanisation.

Fordson – The Powerhouse of Dagenham

No name is more closely associated with the mechanisation of British agriculture than Fordson. From the Model F to the wartime Model N, Fordson tractors rolled off the line at Dagenham in vast numbers; nearly 490,000 between 1939 and 1945 alone.

The Model N became a post-war icon, its steel wheels and minimalist silhouette familiar across muddy fields. Though born in the USA, Fordson became a British standard; reliable, affordable, trusted. The E27N Major and diesel-powered New Major cemented Fordson’s legacy into the 1960s.

For many, it was the only name they trusted to pull the plough.

Massey Ferguson – The World’s Finest Light Tractor

By the late 1950s, the Massey Ferguson 35 - with its red finish and triple-triangle badge; marked a new era. Born from a 1954 merger of Ferguson and Massey-Harris, the MF35 turned the tide by 1957.

Its advanced hydraulics, diesel power, and compact build made it ideal for the global market. Farmers appreciated its reliability, ergonomics, and versatility.

Described in period advertising as “so very popular,” the MF35 became the people’s tractor; a lasting symbol of modern farming.

The Engines of Enterprise – Just Down the Road

Shepherds of Junction Lane – Wood into Work

At the heart of Burscough’s post-war manufacturing stood Shepherds, a high-volume factory producing wooden handles for tools — spades, hammers, hoes, and more.

Supplying national toolmakers, Shepherds drew on local sawmills and skilled returnees from the war. It was both employer and informal craft school, shaping young apprentices and providing vital fittings for post-war rebuilding.

Superwoods of Platts Lane - timber

Location & Industry: This staff photo places Superwood’s at the Platts Lane sawmill; active from the 1940’s to 1980’s, based Ormskirk Advertiser archives

Ownership: Bruce Smith, for many his house and its flower gardens were synonymous with Burscough

Elkes and Fox – The Biscuit Boom

Originally based in Uttoxeter, Elkes expanded through association with Fox’s and established a presence in Burscough — contributing further to the town’s postwar food economy.

Laverys of Redcat Lane – The Cake Boom

Laverys was a major cake manufacturer. After wartime rationing, demand surged — and Laverys met it with batch baking on an industrial scale. Women cycled in from Rufford and Holmeswood, while young men delivered to Liverpool and Preston.

Its tins were familiar in Lancashire homes, and its wages reliable. Laverys helped Burscough thrive; without the grime of the city.

Abbey Kiln Brickworks – Built on Clay

Toward the edge of Burscough, Abbey Kiln Brickworks turned local clay into bricks for schools, farms, and homes. Brickyard work was hard but well paid. Its smoke and fire became familiar; and its products essential in regional development.

The Sawdust Economy – Sawmills and Timber Yards

Burscough’s sawmills supplied raw timber for Shepherds, local builders, and joiners. These family-run operations; all saws, sheds, and stacked logs, underpinned a network of micro-businesses in rural construction and carpentry.

They helped fuel a quiet industrial revolution.

Burscough’s Working Rhythm

What connected these industries was a rhythm: biscuit girls on bikes, forklift tines clattering at Junction Lane, and pub talk of orders and overtime. The roads, canal, and railways gave Burscough mobility; goods moved in and out, ideas too.

It was a revolution hidden in hedgerows and carried out in smocks and aprons.

Conclusion: Making, Shaping, Baking – The Burscough Way

Between 1947 and 1966, Burscough was more than a farming village or a railway stop. It was a hub of modest yet essential industry.

Firms like Ainscoughs, Shepherds, Elkes and Fox, and Laverys weren’t just businesses; they were anchors of local identity. Their legacy lives on in the stories, tools, and taste of West Lancashire. These businesses combined with the growing agricultural and produce merchants to create a hugely positive identity.

A New Kind of Harvest

By the end of 1960, the fields around Rufford still rolled out in neat lines; but something had shifted. The harvest was no longer just lifted, sacked, and sold. It was washed, peeled, sliced, and sealed.

In Burscough, the Martland family had begun crisping spuds in a modest outbuilding: a hand-fed slicer, a bubbling vat of oil, and a wire basket that hissed like a kettle. No brand yet; just “Martlands.”

Over in Aughton, Tattis Crisps had a sharper name and a more polished setup. Then, in 1962, came Golden Wonder in Widnes; the giant. Their lorries had already appeared in Preston and Southport, but the new factory was a game-changer. To lads in Rufford, it signalled both opportunity and warning: something bigger was coming.

By 1962, spuds weren’t just judged by flavour. They were grown for texture, fry quality, and shelf life. The best potatoes no longer ended up in stews and chip shops; they ended up in packets.

The Martland’s of Burscough was more than crisps; they were farmers and merchants with a rich heritage. James Martland (1841–1904) had a profound and lasting impact on farming and the potato trade in Burscough and beyond.

Farming Legacy

Origins: Son of William Martland, a farmer from Moss Lane, but James chose a different path.

Self-Made: By age 20, he left farming to become a produce dealer or ‘badger’, delivering goods to Bolton, Liverpool, and other markets.

Land Ownership: Eventually acquired over 600 acres of farmland in the Burscough area through purchase or tenancy.

Motto: “You must put something in the land if you want to get something out” -he spared no effort or cost, and his crops thrived even in poor seasons.

Potato Pioneer

Innovation: Saw the commercial potential of potatoes and revolutionised their role in local agriculture, replacing corn as the staple crop.

Market Expansion: Opened up new potato markets both in Britain and abroad, making the potato a major commercial crop in West Lancashire.

‘Potato King’: His operations were so vast he was nicknamed the “Potato King of the World”.

Global Influence

Founded and chaired the Potato Merchants’ Steamship Company, which shipped potatoes from Jersey to Holyhead, Fleetwood, Preston, and beyond - with up to 13 sailings a week in season.

Had offices in Jersey, St. Malo, Liverpool, Lincolnshire, Dundee, and more.

Exported to Belgium, Germany, America, and other countries.

Diversification & Infrastructure

Also pioneered oatmeal manufacture, starting at a watermill near the Priory and later building a modern mill on Mart Lane (1885–87).

His business, James Martland Ltd., founded in 1875, grew rapidly and diversified into coal supply by the 1890s.

Family Continuity

His son, Walter Martland, inherited the business and continued to expand it.

Walter also contributed to land drainage, sat on the Crossens Catchment Board, and continued promoting Jersey potatoes locally.

Together, James and Walter Martland helped transform Burscough into a regional powerhouse for potato and produce trade - blending agricultural skill with global commerce. They left a legacy that helped shape the identity of West Lancashire farming well into the 20th century.

Fame Beyond Potatoes: When the Royal Train Slowed at Rufford

They told the story so often it didn’t matter whether it was true.

One summer morning - 1958, some said; others swore ’56 - the Royal Train passed through Rufford. It was heading north, perhaps to Balmoral or maybe just Preston. The details blurred. One thing didn’t: it slowed.

The reality was the 13th March 1955.

A figure was seen — slim, poised, in a pale dress — at the window.

“Might’ve been the Queen,” they said.

“Princess Margaret, more likely,” said another.

“She had porcelain skin,” someone added.

“She looked bored,” came the reply.

Whether or not royalty waved, the memory stuck. It became a local truth — part anecdote, part badge of pride.

School Dinners, Coaches, and Morris Dancers

The school dinners still arrived lukewarm - metal canisters in a battered green van from Ormskirk. Mrs Yates, the dinner lady at Holmeswood School, would lift the lid like a stage magician. Corned beef hash, mashed swede, sponge pudding swimming in separated custard.

“Fill your boots,” she’d say. And we did.

Schools in Holmeswood, Rufford, and Ormskirk were changing. Some boys began taking the 11-plus more seriously; pushed by mothers who’d served in the Land Army and wanted shirts and ties, not sacks and boots. Others leaned toward haulage, mechanics, or the new agricultural colleges cropping up across Lancashire.

Trips became a thing: Blackpool, Southport, sometimes even Morecambe. The Tonks family reportedly polished up a flatbed, strapped benches in the back, and took a school group off for the day. Coaches were coming; with uniformed drivers in pristine white coats. Holmeswood Coaches now had three fully enclosed buses. Contracts to take children to the regions Grammar Schools were up for grabs.

The lucky few who rode them home could boast for weeks.

And the girls? The Morris dancers were everywhere; bright sashes, tin bells, paper flowers in their hair. The Rufford troupe had flair: outfits stitched by aunties, bits borrowed from older sisters. Practice was followed, occasionally, by flirting.

From Blight to Bright Ideas – The Science of the Spud

The humble potato had come a long way since the blight years of the 1840s. By the 1920s, British scientists were working to ensure those dark days didn’t return.

1920s–30s: The Ministry of Agriculture introduced official trials and certification schemes to prevent diseases like blackleg, wilt, and leaf roll virus.

Seed certification: By mid-century, seed potatoes were labelled Pre-basic, Basic, or Certified - each level requiring stricter controls.

Ware potatoes: The ones for eating; chipped, mashed, or boiled still needed careful storage. A bruised spud could ruin a clamp.

Varieties boom: Majestic and Arran Pilot dominated early years; King Edward stayed the roast king. By the ’60s, names like Maris Piper, Pentland Dell, and Wilja entered the conversation.

The National Union of Farmers, in 1950, nominated Mr. W.E Aspinwall of Carr Farm,Lathom to be their member on the Potato Marketing Board. In 1972 playing schools football for Rufford against St John’s, Burscough I would meet Carl Aspinwall and together we would start Hutton Grammar School in 1973.

The Ormskirk Testing Station

The National Institute of Agricultural Botany (NIAB) took over the Ormskirk Potato Testing Station in 1920. It became their first regional outpost, specialising in virus testing and varietal trials.

A 1935 Ormskirk Advertiser article hailed it as vital to the potato trade; reducing varietal confusion, increasing yield, and improving quality. Dr R.N. Salaman’s Synonym Committee helped growers avoid buying the same variety under three different names.

The station closed in 1940 due to wartime constraints, but its influence spread. Today, NIAB still leads in potato testing; using ELISA and PCR methods to detect viruses like PLRV and PVY.

Seed health, disease resistance, and yield performance; all began with those early field trials in West Lancashire.

From Clamps to Crisps – Innovation in the Fields

Mechanisation took hold:

Second-hand Massey Ferguson 35s appeared; narrow wheels, leaking hydraulics, but dependable.

Ashcrofts and Caunces tried NPK blends, experimented with ploughing depth, trialled green manure.

Contract growing took off; especially for chippies and early crisp makers.

Varieties shifted: Majestic and Pilot faded. Pentland Dell, Maris Piper, and Wilja rose.

Petrol and Pubs

The Fermor Arms hosted Saturday singalongs; piano in the corner, pints on the ledge.

Ford Anglias, Zodiacs, Consuls with racing stripes lined the road. The boys at Bispham and Rufford garages turned spanners instead of spuds.

The old hoes still hung in barn shadows; ash handles darkened by sweat. But now, tractors hummed to life before dawn, sorters clattered in the yard, and even potato grading had gone hydraulic.

Progress came slowly. Then suddenly.

Potatoes and Progress

Clamps were covered with hessian and lime.

Curing sheds were trialled by innovators like the Martlands.

Chippies wanted clean, snap-frying spuds; no blemishes, no muck.

Ware vs. Seed: the difference mattered more with every season.

Sons went to Liverpool docks, Ormskirk garages, or Manchester Polytechnic.

Daughters joined accounts departments or secretarial schools.

The potato remained; but now as part of a broader network.

Rows and Rudges: The Language of the Land

In Rufford, you knew where a man was from by how he spoke about soil.

Furrow: the trench left by the plough.

Ridge: what rose between - the planting ground.

Row: the visual line, straight or curved.

Drill: a product of machines, measured and precise.

Rudge: a word half-swallowed by time, still used by old hands who remembered horse paths and soft-footed ploughmen.

“No spud grows straight in a rudge,” they’d say, “but it’ll still boil just fine.”

Between the Rows and the Roads

By 1962, Rufford hadn’t changed on the surface - fields still furrowed, tractors still coughed to life at dawn. But underneath, the roots had shifted.

The spud, once shared in sacks and baskets, was now tested for virus resistance and trialled for yield curves. Farmers used charts as often as they used boots.

The forge still hissed at Lingard’s - but now it sharpened blades for graders, not horseshoes.

And through it all, the people adapted. Quietly. Without fuss.

The land remained. It still shaped them. But it no longer defined them alone.

And so the village moved forward — not all at once, but row by row, road by road.

The spud endured.

Mark, this is a wonderful story in terms of its depth and breath. Better for re reading!

It’s opening in the kitchen and Mum’s recipes and closing, talking about boys with spanners and go faster stripes.

Thank you again

Excellent read Mark, I’m learning more and more about our West Lancashire home.