The Story of the Rufford Spud

Episode 5: The Potato Men of the 1950’s. From Victory to Vocation; how Rufford’s sons returned to reshape the land.

Section 1: VE Day and the Long Road Home

Victory in Europe was declared on 8 May 1945. In cities, they danced in the streets. In Rufford, they stood quietly at the edge of the fields. The radios crackled, the church bells rang, and across the village, hands paused mid-task. Not out of shock—but because they knew: the hardest work was just beginning.

The Ashcrofts, the Caunces, the Bridges; names that had tilled Rufford’s soil for generations, began welcoming their sons home. Some returned in uniform, boots still caked in foreign mud. Others came back quieter, carrying not medals but memories. One by one, they filtered back to farms that had carried on without them; kept alive by daughters, widows, lads not yet old enough to shave, and mothers who never stopped digging.

At Thornton Farm, John Ashcroft’s brood regrouped. The elder sons, hardened by years in South Africa, North Africa and Italy, walked the old boundaries with new eyes. The daughter who’d served with the Land Army in Gloucestershire now knew her way around vans and cattle, and had met her future husband. And the youngest; still an apprentice sheet metalworker in Bolton.

Section 2: A Different Path – Uncle Linton and the Haulage Horizon

Not every returning son stepped back into the fields.

For Uncle Linton, the war ended with more than just a demobilisation; it ended with a loss. His father, a lifelong farmer, had died in November 1947. The timing couldn’t have been crueller. The war was over, but the farm’s future was suddenly uncertain. Without its head, the land stood still; and potentially, so did Linton.

Faced with the weight of expectation and the shadow of grief, he stayed with his decision to drive lorries: he didn’t take up the plough. He took the wheel.

Linton became a driver for Caunce of Rufford, one of the first of a new breed; part haulier, part middleman, part field ambassador. He wore boots, not brogues, and knew every lane from Holmeswood to the Liverpool docks. His cab became his office, his route sheet his rhythm.

He didn’t talk much about Burma, where he’d served with the RAF, nor about the long journeys home. But on the road, he found something of his own; movement, purpose, and a livelihood that kept him connected to the land, even if he no longer walked it row by row. He was known to every farmer in the district.

People said he could reverse a flatbed with half a cigarette still burning and never spill a sack.

Section 3: First-Hand Memories – WW2 to the Coronation

Dave Magill’s Sandy Way Memories

Not everyone in Holmeswood was born there. Some arrived by train, or by chance. Dave Magill was one of them - a Bootle lad evacuated during the Liverpool Blitz, his childhood reshaped by travel, fear, and friendship.

He remembered nights in the air-raid shelter behind the Mons Hotel, listening to the drone of German planes overhead. Then a sudden move to Anglesey, immediately in the aftermath of a direct hit adjacent to the Mons; then Mawdesley, and finally to Sandy Way, Holmeswood, where he lived in a cottage that belonged to the Porter family; a village with kind, steady people who gave him space to be a boy again.

Holmeswood became his playground and his refuge. He fell in with Ken Tunks and George Rimmer, two local lads who knew every foot of the lanes and fields. On Sundays, Dave would often be found with the Rimmer family, playing long, legendary games of “Find the Lady.” Dave remembers people coming from miles around to play cards; and at times, two packs were needed to make a game possible for the numbers crowded into Mrs. Rimmer’s family home.

People travelled from miles around for those Sundays at Mrs Rimmer; small in stature but big in personality. Dave mentioned, that he once got locked out of his house by his brother Stanley, who refused to let him in as he had stayed watching card games way beyond his bedtime. Dave ran off, hid, and had to bed down under steps up to a barn, wrapped in an old sack, and more laughter than warmth.

There was work too, even for a boy, especially on the farms. He remembers Fir Tree Farm, Sutton’s Dairy, Tillotson’s, Dan Harrison’s Farm, and Singleton’s, where he’d help with lifting, sorting, fetching water or milk, and moving crates—once leading a horse to Mere Brow Smithy and back again. Not far from him lived the Lettuce King—Harry Ball—and not far from that, the Cauliflower King, Dan Harrison, two local legends whose nicknames were worn with pride.

In 1947, Dave’s sister Avril was born at Sandy Way. His older sister Barbara, who had served in the ATS with Jean Rimmer of Rufford, later married Jim Sephton, a key figure in Rufford Cricket Club. His eldest brother, Stanley, had joined the RAF.

He also recalled with a twinkle the day of Phoebe Rimmer and Les Staziker’s wedding; a proper local knees-up. Dave vividly remembers getting dressed up as pirates so they could “hold up” the wedding car, which they did—and were rewarded with a shilling. The scene of the crime midway between Rufford and Holmeswood, outside the entrance to what is now W&M Thompson.

There was joy even in hard times. He remembered Brick Kiln Lane and the 1953 Coronation, where schoolchildren at Holmeswood and Rufford Schools were given silver spoons to mark the day. Dave was sat watching the Coronation on one of the few TV’s in the village, with Jim Sephton’s parents at Brick Kiln Lane, before being reminded he had to go and collect his silver spoon from Holmeswood School.

Mechanisation and Haulage

By the late 1940s, the old rhythms of Rufford and Holmeswood farming; horse-drawn carts, hand-picked rows, sweat-soaked sacks, were being steadily replaced. The new rhythm was louder. It came with the rattle of trailers, the chug of grey Fergie tractors, and the puff of black smoke from the back of flatbeds loaded with seed sacks.

Tunks were developing a business as produce merchants, with tomatoes and potatoes central. As Dave recalls, they were among the first to embrace this shift. With local drivers often at the wheel and lads like Dave Magill along for the ride, they delivered and hauled produce across the moss. One day it might be potatoes from Lincoln to Manchester, the next vegetables to hospital canteens in Southport. Lorries were quickly becoming as vital as the men themselves.

Some of the old hands, like my Uncle Linton, now driving for Caunce’s, had to adapt fast. The roads weren’t always ready, the lanes often flooded or potholed, but the ambition was there. West Lancashire was feeding a nation still living under ration books, and no one had time to wait for smoother tarmac.

The nicknames from the fields lingered even as the machinery arrived. There was Harry Ball, the “Lettuce King,” known for his perfect rows and clipped speech, and Dan Harrison, the “Cauliflower King,” who ran his fields with military precision. They might have chuckled at the new gears and gadgets, but they also knew the world was changing—and fast.

And the spuds? They weren’t just being lifted anymore. They were being studied.

Just outside Ormskirk, a new Potato Research and Marketing Centre had taken root—part science lab, part advisory hub, and quietly revolutionary. Here, varieties were trialled, growing conditions measured, and futures tested in soil and paper. A 1953 article in The Ormskirk Advertiser reported:

“The most marked improvement was noted in the Sutton variety when grown on lighter land under mechanical grading conditions.”

It was proof that West Lancashire wasn’t just working the land—it was leading the nation in how to grow it better.

The era of steam and spade was shifting toward something else entirely: science, speed, and sacks by the tonne.

Women in Uniform

While the men of Rufford and Holmeswood returned to farms and wagons, many of the women carried on with quiet pride and powerful stories of their own. Two such women were Barbara Magill and Jean Rimmer—both of Rufford, both serving in the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) during the war.

Barbara, Dave Magill’s older sister, enlisted young and was stationed first at Ormskirk. She was trained in telecommunications and vehicle logistics, often working long shifts in draughty depots, dispatching messages and maintaining records of truck movements across the Northwest.

Jean Rimmer, elder sister of Dave’s friend George, served on similar duties in Ormskirk, where she was known for her methodical calm. Dave has wonderful memories of the Rimmer family and jean was on of those 9 siblings.

Their uniforms may have looked plain, khaki wool and stiff collars; but to the villagers back home, they represented purpose and possibility. These were not girls waiting for the world to resume; they were part of keeping it going.

After the war, Barbara returned to Rufford and, in time, married Jim Sephton, a local with deep roots in Rufford Cricket Club. She kept her organisational talents sharp, managing the ladies at the cricket club with the same precision she’d once applied to army rotas. Jean Rimmer remained a quiet cornerstone of the village—never one for fanfare, but always remembered for her wartime steadiness and sharp mind.

The 1953 Coronation

By 1953, the village had changed in small, stubborn ways. The trucks were bigger. The fields straighter. Some houses had new fences, others a fresh coat of whitewash. The war was still present in memory, but Queen Elizabeth’s Coronation offered a moment to look forward; a bright ribbon tied around the post-war decade.

At Holmeswood School, the children were handed commemorative silver spoons, stamped with the Royal Crest. There was squash and sponge cake, and paper crowns folded with care. For many evacuees who had stayed on in the village, it was a day that confirmed something unspoken: they belonged.

Brick Kiln Lane was bunting-strewn, with children running races between parked bicycles. Radios crackled from open windows as families gathered to listen to the events from London. Few had televisions, but no one seemed to mind. The feeling was one of cautious pride; both in the young Queen and in what the village had weathered to see her crowned.

Section 4: Loss, Duty, and Departure – 1947

In 1947, the Ashcroft family faced another turning point. John Ashcroft; my grandfather, died, leaving behind a legacy rooted in soil, family, and hard-won wartime resilience. He had held Thornton Farm together through years of rationing and absence, guiding sons, daughters, and neighbours with a steady hand and unspoken strength. He had been at the centre of village sport and was Secretary of the Rufford Agricultural Show.

His passing was more than the loss of a man. It marked the end of an era: the generation that had ploughed by horse, lifted potatoes by candlelight, and measured success in full clamps and clean boots. With him went the quiet rituals of pre-war Rufford farming life; the unhurried walk of the land, the old jokes traded over hedgerows, the knowledge passed down by action, not explanation.

But his legacy endured. In his children. In the furrows they turned. And in the decisions they now faced.

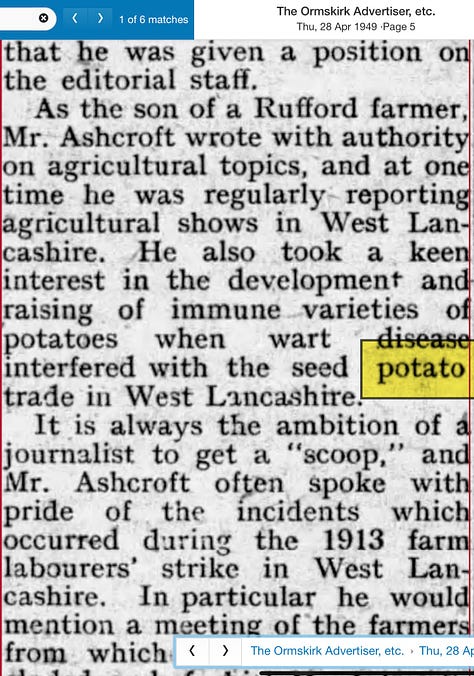

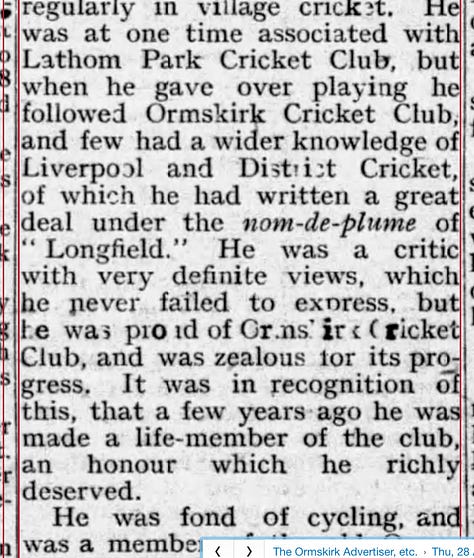

Two years later my Grandad’s brother Edward, was to pass away. He was known for his love of farming and cricket; and was the Editor of The Ormskirk Advertiser. As i constantly access their archives to add research to my photo essays, there is a huge sense of pride.

Section 5: The Gears Begin to Turn

By 1948, the unmistakable cough and roar of diesel engines had become part of the village soundscape. Fordsons rumbled through fields that once echoed with the creak of harnesses. The horses, loyal and steady, were gradually led to pasture; retired not with fanfare, but with respect. A new generation of machinery was taking over, led by the likes of the grey Ferguson TE20, already earning a quiet legend among West Lancashire farmers.

It was the age of the “mechanical handshake.” Deals were struck over bonnets, not barns. Oil-stained gloves replaced calloused palms. And in farmyards across Rufford; at Church Farm, Brick Kiln, Holly Lane, and beyond, the first wave of mechanisation took root.

But the field wasn’t the only place where things were changing.

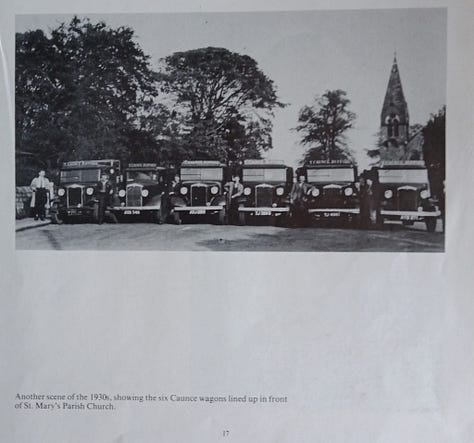

The roads began to hum with purpose. Ex-army lorries were reconditioned and put to work hauling spuds, sacks, and livestock. Potato merchants and budding hauliers like the Caunces and Southworths transformed simple village logistics into something bigger. A new kind of man emerged, the potato wagon driver, part grower, part trader, part navigator of the battered British road network.

Many remember it. Here’s what it might have felt like for a youngster

“The jolt of the cab beneath you as your dad ground the gears into place. The tang of diesel and sackcloth. Flour sacks doubling as cushions. The way he’d point to passing farms and name the families, the soil type, the yield of last season’s crop. Riding shotgun wasn’t just a treat; it was an education.

He’d drive to Liverpool’s Fruit Exchange or to far-flung spots like Blackburn market. You’d listen as deals were done at the back of wagons. Sometimes in cash, sometimes in promises. And always with a nod that meant, “See you next week.” Memories.”

These were the Potato Men of Rufford; quiet innovators, armed with order pads and instinct. They didn’t talk about legacy. They lived it.

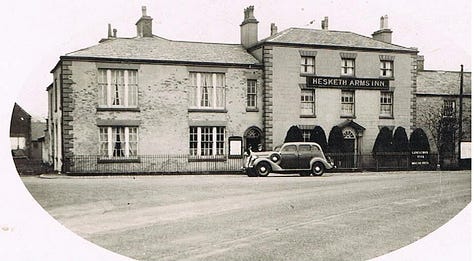

Section 5: Friday Nights at the Fermor and the Hesketh

By the 1950s, Friday nights had found their rhythm in Rufford. The clatter of crates and the low rumble of returning wagons gave way to the hush of field boots changing for pub shoes. The workweek didn’t end with a whistle; it ended with a pint. Maybe a mid-week Darts and Dominoes league.

At the Fermor Arms, down near the station, hauliers and farmers slid into well-worn settles beneath an ornate ceiling and old tobacco smoke. The talk was of tonnage and routes, of axle grease and axle weights, and whether the bloke from Banks had undercut the going rate to Liverpool’s Fruit Exchange. You didn’t need a phone; just a face, a nod, and maybe a quick note jotted on the back of a cigarette packet.

Over at the Hesketh Arms, across from Thornton Farm, it was much the same. A little louder, perhaps. More jokes, more farmers’ tales. Someone always had a story about a flat tyre on the Tarleton Moss, or a load of carrots that came loose on Sluice Lane. They were stories told not for sympathy, but for the joy of recounting near disasters with a wry grin.

And of course, there were the pints. Beer pulled slow and steady. No rush. The weekend would come soon enough, and with it, another few tonnes of spuds to shift before market.

Young lads listened in from the corner. If you were lucky, you got a dandelion and burdock or a sneaky half of mild. If you were very lucky, you were asked to run outside and check the weight ticket someone had left in the cab. That was how you learned.

These pubs were more than watering holes. They were boardrooms, break rooms, and bulletin boards. Business was done with a nod, a pint, and a promise. It wasn’t all potatoes, of course; but somehow, it always circled back to the land.

Footnotes from the Fields: The Great Egg Explosion

“They say a man once cycled through Rufford during the war, front basket brimming with black-market eggs. A sharp trader, no doubt—until a German plane flew low over the village and dropped an incendiary bomb nearby.

The blast didn’t hit him, but it hit close enough.

The bike bucked. The man flew. The eggs; dozens of them, smashed on impact, decorating the road in a splatter of wartime protein. No one quite remembers his name. Some say he limped away cursing Luftwaffe precision. Others say it served him right for charging sixpence an egg.

Whether true or tall tale, it’s a story that stuck; yolk and all.”

Section 7: Steam, Steel, and the Spud Supply Chain

By the mid-1950s, Rufford’s potatoes were no longer just local fare. They were part of something bigger; a network of fields, roads, rails, and markets that stretched from the mosslands of Lancashire to the frying pans of industrial Britain.

The black soil, long prized for its drainage and richness, had become a quietly humming engine of post-war recovery. From Scarisbrick Moss to Tarleton, Banks to Burscough, earlies, second earlies and maincrop potatoes were lifted, sorted, bagged, and sent; by truck, by cart, sometimes even still by rail.

At the Southport and Ormskirk sidings, wagons were loaded with sacks bound for Liverpool, Manchester, and beyond. Some still remember the way the steam rose against the cold morning sky, the hessian sacks stacked high and tight, tied with twine and stencilled with names that meant something: Ashcroft, Bridge, Caunce, Rimmer.

Road haulage took over quickly. Ex-military trucks were repurposed, liveried in rough hand-painted script. “W. Martland – Produce & Haulage.” “Caunce & Sons – Potatoes” Every lorry told a story: of family effort, of village-scale enterprise expanding toward something commercial; but never corporate.

Even the chip shops were shifting. Regular supply chains began forming, and farmers who once sold sacks by the barrow now negotiated by the tonne. Tarleton’s tomato glasshouses and the carrot fields of Halsall were pulling in new markets; but Rufford, still, remained a centre of the humble spud.

And behind it all were men who never called themselves entrepreneurs. They called themselves “drivers,” “growers,” “potato men.” Men who changed spark plugs in the dark, bartered sacks in back yards, and timed their loads by the tolling of Rufford Church bells.

Section 8: The Youngest Ashcroft – From Burscough to Boogey Street

Not every Ashcroft stayed close to the fields.

The youngest son, my dad, had been posted at Burscough Camp just after the war’s final stretch, working with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME). He was handy with engines and sharp with a spanner, skills that kept him close to home… for a while.

But in the late 1940’s/early 1950’s he was deployed to the Far East. First Singapore, then on to the jungles of Malaya; part of Britain’s post-war operations during the Malayan Emergency.

He rarely talked about it. But you heard the fragments.

The troop ship, packed with thousands of young men, where one night a dazzling female figure took to the stage. The crowd hushed; then roared, murmuring that no-one had seen a women on board. Then being told it was Danny La Rue, in full sequins and command of the deck.

You heard about Boogey Street, the humid chaos of Singapore nights. And the time he went AWOL after attending an Indian funeral, returning to base quietly, reprimanded, again. Family folklore is of my Grandma continually taking off and sewing back on his Corporal stripes. His commanding officer liked him; especially for his cricket and football. He was once pulled off manoeuvres to represent the Army in a match at the Singapore Cricket Club.

While others scrawled letters home from the jungle, he fixed trucks in the sweltering dark and made a life out of keeping things running; on two wheels, four wheels, or none at all.

He had left Rufford. But he carried it with him. In the way he worked, the way he watched the weather, and the way he never wasted a thing.

Closing Reflection: Where the Road Led

By the close of the 1950s, the furrows of Rufford had become more than lines in a field. They were lines in a ledger, tracks on a road map, routes to ports and promises. The potato men had built something; without ever naming it. They just got on with the job.

My Dad was one of them. A man of few words but many miles, who knew the weight of a sack by the drag on his boots and could judge a field’s yield by the colour of the leaves in June. He drove, lifted, laughed, and leaned on the same bar every Friday, pint in hand, with the land still on his boots.

He didn’t call it legacy. But it was.

Because through men like him; and the women who stitched the sacks, fed the pickers, and ran the farms in wartime silence, Rufford found its footing in a changing world. The fields didn’t vanish. They evolved. And the spuds still came up from the black earth, stubborn and proud.

Some roads led away, to factories, to shops, to docks. But some roads stayed right here, winding past the same hedgerows, the same sluices, the same names carved into wood above bar doors.

And that’s where we find them still: the stories, the soil, and the wheels that kept turning; long after the war was won.